Bucca & His Role in the Modern Craft

At one point, someone asked me: “Hey I’m interested in the ins and outs of the Bucca but to be entirely honest I can’t make heads or tails of much of the literature around them. Is Bucca Dhu the same as Odin and is the Grand Bucca the same as Baphomet?” In my attempt to sufficient answer this question, I was spurred to write the following research piece.

In many iterations and interpretations of the occultic arts often categorized loosely as ‘modern traditional witchcraft,’ a deific figure frequently called ‘The Horned One’ amongst innumerable similar titles is regarded as the principal Witching God of a given tradition, as well as the chief initiator of the Cunning Flame itself. It is a commonly embraced belief within most currents of practice that tend to fall under this banner of traditional witchcraft,’ that in Old Britain, the god of rural witches was often referred to as Devil. It is ostensibly for this reason that this is still the case for many traditionally based practitioners in the surrounding areas, including the Crafters of Cornwall.

The Devil of the modern traditional witchcraft is, of course, rarely equated directly with Satan as he is depicted in Abrahamic faiths, but is instead regarded, as Gemma Gary puts it, “an old chthonic folk-god of the land mysteries and seasonal changes (particularly the Autumn and Winter months), weather (particularly storms), death mysteries and the unseen forces and gnosis of use to witchcraft. ” She likewise states that “To traditional witches and Cunning folk in Cornwall, in particular the Penwith region, the old Horned One is known as Bucca, and in West Devon as Buckie.” (Traditional Witchcraft: A Cornish Book of Ways pg 77, by Gemma Gary)

One aspect of the Bucca found in Cornish lore, and embraced within the paradigm of Gary’s practice, is that he emanates into the dichotomy of Bucca Gwidder `and Bucca Dhu’- otherwise known the White God and the Black God.’ Bucca Dhu is generally seen as the Devil of the previously discussed rural British folk-belief, and is associated with storms, darkness. and the winter months Conversely, Bucca Gwidder is generally associated with fair weather, light, and the summer months. As is the case in many other, similar spiritual paradigms, Bucca Gwidder and Bucca Dhu dualistically embody the opposing forces of nature. They are intimately tied to one another, with one always giving rise to the other in an infinite cycle of death and rebirth. What’s more. while I can’t seem to find historical evidence for it at this point, Gemma Gary and the coven of Ros an Bucca venerate a mystic triplicity as well, in the form of a conjoined Bucca, known as ‘Bucca Gam’, or the ‘Grand Bucca’. This union of opposing forces is said to result in the embodiment of an ‘Androgyne of the Wise’, a concept which mirrors the attainment of the Alchemical Magnum Opus – also called the Rebis (‘Double Matter’) or ‘Divine Hermaphrodite’ – which was frequently identified with the attainment of complete wisdom. According to Gary, “The Grand Bucca and the great Horned Androgyne, the Sabbatic Goat and Goddess-God of the witch-way. For some the Grand Bucca is simply referred to as Bucca, being the whole, with the two opposing aspects of that whole being given the distinction of Bucca Gwidder and Bucca Dhu. In Bucca we find the resolving of all opposites, the traditional candle betwixt the horns symbolising the light of ‘All-Wisdom’, and the mystic state of ‘One-pointedness,’ which is the ultimate goal of the witch and is the light that illumines the Cunning Path.” (Traditional Witchcraft: A Cornish Book of Ways’, pg. 84, by Gemma Gary)

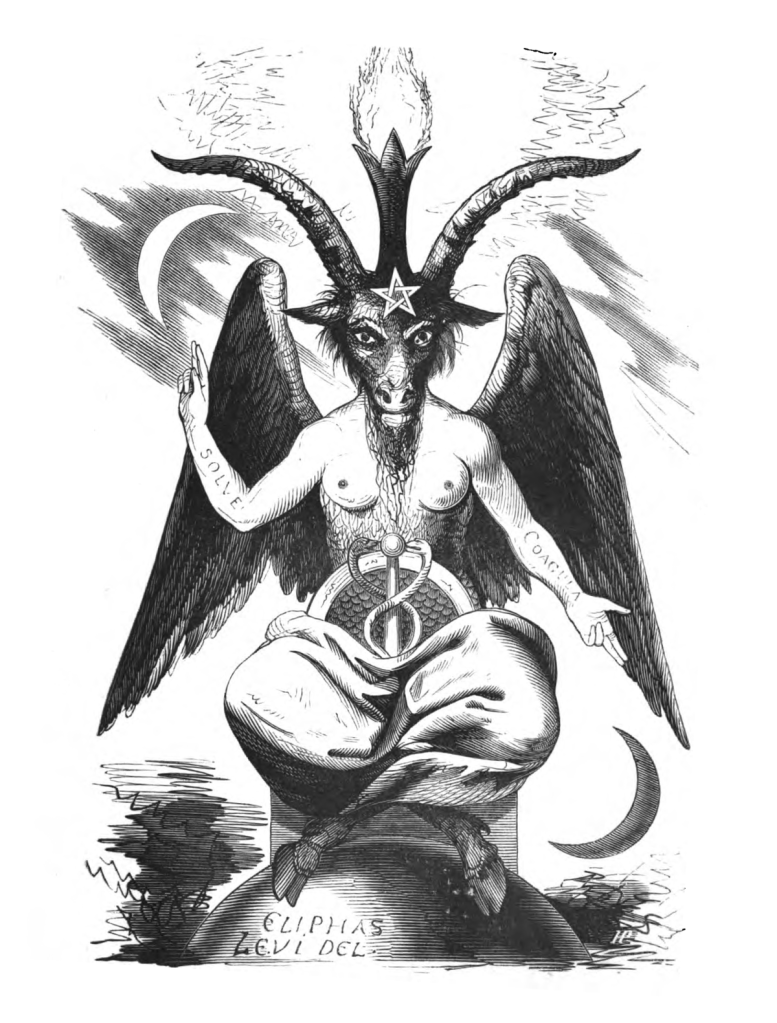

Regarding the connections between Bucca Gam and Baphomet, I think it largely comes down to the fact that it’s relatively rare for modern occult practices to acknowledge deities who are explicitly intersex, with the best-known example of the Divine Androgyne being Baphomet – a being invented by Crusaders in order to demonize the Knights Templar, and then eventually taken up and popularized by occultist Eliphas Levi.

Now, when it comes to the question of syncretic connections between Bucca and Odin/Woden, it primarily comes down to their roles within the concept of the Wild Hunt. As many people know the Wild Hunt is an important folkloric motif, which describes the shepherding of a ghostly procession across the sky by a powerful mythic figure. In the Germanic world, the leader of this convoy was commonly identified with Odin. Within much of the known Celtic lore, this phantom band was attended and directed by great spectral hounds, known by a wide variety of names. In Cornwall, the Wild Hunt is generally associated with folkloric figures known as the ‘Devil’s Dandy Dogs,’ also called ‘Dando’s Dogs,’ however, it may also be associated with Bucca.

As Gary put it, “On dark and cold nights of winter, Bucca Dhu is also described as riding a great black horse with blazing red eyes and smoky breath. Such lore surrounding Bucca Dhu is cognate with the widespread folk traditions of the Devil and Odin/Woden, as leaders of the Wild Hunt, which in British tradition runs along the Abbot’s Way towards Cornwall; the last stop en route to the Otherworld.

I am yet to come across anything in the folkloric record that matches these particular details, however, it would seem that there is some traditional connection there. For instance, Bucca does demonstrate characteristics of the Wild Hunt in certain versions of the classic Cornish play “Duffy and the Devil” (sometimes called “Duffy and the Bucca”.) This link to Odin is further cemented by the fact that Bucca Dhu is demonstrably connected to the Devil in Cornwall, and the Devil is sometimes said to lead the Wild Hunt, creating I an archetypal framework within which both Odin and Bucca fit.

Now for the historical/folkloric background I promised.

According to most relevant sources, Bucca was traditionally described as a form of male Sea Spirit who inhabited coastal communities and their mines during storms-often in the form of a sort of hobgoblin.

Many agree that the origins of the Bucca likely relate to faery beings such as the Pwca Púca, and Puck of Welsh, Irish and English folklore, respectively, though he also seems to share characteristics with the mermaids of Welsh and Breton mythology-known variably as Morgens, Morgans, or Mari-Morgans.

In one folktale, loosely known as ‘The Sea Bucca of Lamorna’, Bucca was a lonely creature who had once been a human prince, before being cursed by a witch. He was described as having the dark brown skin of a conger eel and a mass of seaweed for hair, as well as a penchant for swimming in the open waves, sitting among the rocks, and/or resting in hidden sea caverns. He was fond of children and assisted the Lamorna fishermen by driving fish and crabs into their nets and pots, but he was capable of terrible retribution, so they generally kept their distance, but left a part of their catch on the beach in order to mollify him.

However, it’s clear that many accounts on the matter clearly speak of the Bucca as more than simply a faery, or sea creature. As Cornish folklorist William Bottrell put it in his 1870 work ‘Traditions and Hearthside Stories of West Cornwall’, “It is uncertain whether Bucka can be regarded as one of the fairy tribe; Old people, within my remembrance, spoke of a Bucka Gwidden and a Bucka Dhu-by the former they meant good spirit, and by the latter an evil one, now known as Bucka boo.”

In keeping with Bottrell’s account of the Bucca, a number of folkloric sources make note of Bucca’s manifold nature, referencing the existence of a Bucca Gwydden/Gwydder’ (White Bucca) and Bucca Dhu’ (Black Bucca). Each of these accounts agrees upon the respective benevolent and malevolent natures of these incarnations, though it’s interesting to note that there are considerably more reports of Bucca Dhu, or ‘Bucca Boo,’ than there are of Bucca Gwydder.

A 19th Century author on Cornish antiquities, named Rev W.S. Lach-Szyrma, proposed Bucca to be the cultural remnant of an ancient pagan Marine Deity once worshiped in the area, such as the British Nodens or the Irish Nechtans. While claims such as these are primarily conjecture, folkloric records do make note of food being left out on the beaches of the region as votive offerings. In the 19th century, for instance, there were reports of fishermen venerating Bucca with offerings of fish, which were left for the enigmatic Wight upon the shores of multiple local beaches. One of these beaches, particularly well known for its use as a site of propitiation, was located near the Cornish town of Newlyn, known formerly as Park an Grouse (Cornish for ‘the field of the cross’,) where a stone cross was said to once have stood. These accounts, in turn, bear a certain resemblance to reports of offerings provided to the subterranean Knockers of the region, and as such, may signify some form of cultural continuity of pre-Christian Brythonic traditions. In keeping with this theme of the ‘Mine Faery’ it’s also worth noting that Bucca was sometimes described as a tin-mining spirit as well However, Bucca has additionally been historically associated with storms, and in particular with the wind, which was said to carry his voice across the sea in parts of the West Country. In fact, in Penzance, it was once considered normal to refer to storms that came out of the Southwest as ‘Bucca Calling.’ For this reason, among others, it is possible that Bucca would have been more properly labeled a weather deity, as opposed to a deity of the sea itself – a distinction that Gemma Gary endorses enthusiastically in ‘A Cornish Book of Ways.

In Jaqueline Simpson’s ‘A Dictionary of Celtic Mythology’, these marine tempestuous, subterranean, and pastoral themes are tied together when it’s stated that, “In Cornwall, [Bucca] was ‘a spirit it was once thought necessary to propitiate’; fishermen, tin-miners, and harvesters would deliberately leave a few scraps of their food for him, and spill a few drops of beer.

Some said there were two buccas one white and kindly, the other black and dangerous Fishermen applied the name to a sea goblin of some sort, causing a 19th-century vicar [Lach-Szyrma] to refer to the bucca-boo as ‘the storm-god of the old Cornish.’ The origins of Bucca’s association with the devil are murky, but they probably have something to do with the widespread equation of faeries with devils in early modern Britain. This doesn’t exactly account for the Bucca’s role as Witch-Father in traditionalist Cornish witchcraft, but those origins are also somewhat murky. It would seem that, at least on the historical record, this particular role was only truly appointed to Bucca around the time of Ros an Bucca’s formation. This isn’t to say, of course, that there weren’t a quiet few who venerated Bucca ongoingly in Cornwall, but given the inherently cultic nature of most covens, this simply isn’t verifiable. However W.S. Lach-Szyrma’s assertions regarding Bucca as “storm god of the old Cornish” do make explicit reference to the ties between Bucca and the Devil, such as in his 1884 ‘Newlyn and its Piers,’ where he wrote that in the Middle Ages, Bucca was “represented as the Devil.”

This syncretism is also briefly highlighted in Margaret Ann Courtney’s 1890 book ‘Cornish Feasts and Folk-lore’ when it’s explained that, “In the adjacent parish of Newlyn, a fishing village, the favourite resort of artists, a great deal of gossiping on summer evenings goes on around the small wells (here called peeths) […] Opposite one of these wells towering over St. Peter’s church, is a striking pile of rocks, or Tolcarn. On the summit are some curious markings in the stones, which, when a child, I was told were the devil’s footprints; but the following legend which I give on the authority of the Rev.W. S. Lach-Szyrma, Vicar of St. Peter’s, is quite new to me:-

‘The summit of the rock is reticulated with curious veins of elvan [quartz-porphyry] about which a quaint Cornish legend relates that the Bucca-boo, or storm-god of the old Cornish, stole the fishermens’ net. Being pursued by Paul choir, who sang the Creed, he flew to the top of Paul hill and thence over the Coombe to Tolcarn, where he turned the nets into stone.”

With all of these variable, sometimes even conflicting, accounts of who and what the Bucca is, it’s really not a shock that many people find themselves feeling lost when it comes to understanding him, but I hope that this can help to elucidate the subject for some. Resources on the subject are sparse, but they do exist, and a fascinating patchwork of historical and modern perspectives begins to reveal itself if you look for it. Yet, like most things in life his identity will continue to unfold, shift, and evolve over the years to come